Out of Time

I can thank my old teacher, Mr Brack, for one thing. He made me understand that there was something seriously wrong with me. Seriously wrong, not just wrong. Every kid thinks there's something wrong with them. They just hope it isn't serious, either because it's not permanent, or because it's not important.

But climbing ten rows in the school amphitheatre specifically to sit behind me showed it was serious. Serious important. Teachers didn't give kids individual attention in those days. The occasion was a group singing session at my high school when we were taking a short detour through positivity. Michael was rowing his boat ashore, with a group clap at the end of each line to make sure we were all singing in unison. Apparently, this was just the thing to drive away tension between the skaters and our local Sharpies.

I knew that I wasn't clapping in time, but I didn't think I was hurting anyone. A broad set, red faced, bearded man in an aggressively checked shirt clapping angrily next to my right ear implied otherwise. He wasn't even a music teacher. The red and blue pens in his top pocket showed that he was usually angry about maths.

Mr Brack clapped louder the second time I missed the beat to force me into time, and louder still on the third miss. My young self, before I fully understood my condition, believed that if I just tried harder I could get into sync with him. I listened closely and focused all my attention on his hands which I could see out of the corner of my eyes. I was determined to clap the instant I saw his hands move.

It didn't work. I missed the beat each time. He sighed theatrically at the end of the song and returned to the stage to glare at anyone with the temerity to talk while the music teacher was outlining next week's inspiring program. I hung my head down trying not to cry in front of the tougher boys and girls, and wondered what else I could have done. Serious permanent.

#

I know now that I'll always be a little bit behind everyone else. Half a beat, or more annoyingly maybe two thirds of a beat, sometimes even seven eights of a beat. Never a full beat, and never in a rhythm you could argue was deliberate. Not even for a jazz drummer.

It's not because I'm not musical. Though I'm not. I just live in my own little eddy of time. A little bit behind the mainstream. I can see and hear what's going on. If you met me, we could have a conversation. But even if I reacted immediately in my time, your time would have passed on, and my response would be late for you.

Self-understanding didn't come easily. I stuttered through university. Subjects based on written assignments only took five or ten percent off for late submissions. I chose that discount and still got a degree.

I've been able to get by in the public service. Being a bit behind in my deadlines doesn't exactly single me out. And in a cerebral environment, people assume that my answers are slow because I'm thinking deeply about an issue. Anyway, it's remarkable how many people will supply their own answer, usually correct, to questions they've just asked if you just wait for a little while. Even half a beat will do it.

I know I'll never get promoted to a job with an actual office. But I can keep my time sheets in balance. My lateness in the morning is equalised by a delay in the evening. And I can put pictures of Susan and our two dogs on the walls of my cubicle.

Which brings me to relationships. Obviously high school wasn't great with its premium on quick wit, dance moves, and if challenged, fighting ability. Clapping wasn't the only thing that put me at the bottom of the pecking order.

At university my hand always landed in the space my dates hand had just left. But there's someone for everyone, and Susan didn't seem to mind that I was out of step with the world. 'You're just a bit vague," she'd say with a smile when we first met. As we found out, being little bit behind has its advantages in bed.

Understanding that I'd never be valuable in my own right also makes me a grateful partner. Some would say my commitment to Susan makes ours a truly equal relationship. But only if they didn't know my fear that there's no one else in the world who would put up with my personal anachronism.

So, all in all, my timeliness was never a problem in my relationship with Susan. Or it was never a problem until we met Paul.

#

At football matches I can let myself be washed along by the crowd and the patterns of the game without any obligation to sing, clap, or dance in time. And without any consequences if I'm not in time. It doesn't matter if I yell my outrage or approval late. At any time, half the crowd are still trying to figure out what just happened anyway, so usually I fit right in.

We first met Paul at a derby. He was sitting behind us. Like all of us he was helping the referees by screaming out the result of the last sequence of play. Whether it was a foul, obstruction, a throw in, offside, whatever.

Unlike everybody else he was one hundred percent right each time. If he yelled, "Offside", it was offside, and his, "Foul", always predicted a free kick.

Susan turned around and looked him up and down. "Did you used to play? You seem to know what's going on." She looked at me. "We can never figure it out."

He smiled in an embarrassed way at Susan. As we turned around to watch the match again, I could have sworn that I could feel his eyes staring at the back of my head. I turned around again, but he was already looking away.

#

When I'd figured myself out, I'd occasionally dreamt about meeting someone with my condition. What would it be like to have two people a beat behind the song? Would we synchronise with each other perfectly? Would we keep slowing down? But before Paul, I'd never thought that there would be someone who balanced me. Someone half a beat in front of everyone else. Maybe it’s as obvious to you as it is to me now. If there's someone in their own time stream, one that is just a little bit slower than everyone else’s, then it stands to reason that there can be, and most likely would be, someone who's a little bit quicker. Time must balance after all.

#

Paul's football prediction prowess would have been an uncomfortable memory, disconcerting but essentially painless, if he hadn't turned up at work the next week.

Susan was picking me up to go to lunch and waiting in the foyer. I was a little bit late as usual and hurried up to her after getting my pass tangled in the security gate. As I leant in to kiss her cheek she pulled away.

"Oh hi, aren't you the guy from the football?"

Paul smiled. He was already next to us, standing a little too close for my liking. He smiled and nodded.

"So, what are you doing here?" I asked. I had to take a step back to see him properly without throwing my neck out. He was tall.

"I'm one of the new grads," said Paul.

Susan suggested that it would be great if he joined us for lunch so I could give him a few tips. I know I've been in the organisation for a couple of years, but I was pretty sure that none of the grads wanted anything from me. Certainly not Paul. But he tagged along anyway.

#

Over the next few weeks Paul came into our lives. Like all the grads he had friends, but he seemed to like spending time with us.

Susan enjoyed his company. Simple things, like playing Uno, which are boring with me given I'm so slow, were exciting with Paul.

I didn't think much of it. I'm used to being in the back of the queue. I was even amused when the dogs, who pay little attention to my commands, followed Paul at perfect heel.

That was until the singing started.

We'd got into the habit of taking turns at selecting music while we played games.

Why it came into my head, I don't know, but I chose Michael row the boat ashore.

Susan started to sing. It was probably compulsory at her high school as well. She has a good voice, but it's soft.

"Come on, Paul, sing with me," she said.

She would never have allowed me to sing with her and spoil the song.

There was a bit of me that thought that this might turn out to be a master move for me. He had the same problem I do. He's out of time.

Sure enough, his voice wasn't in time with hers.

He started on the second repetition, just a little earlier than her. But his voice was in harmony with hers, and the split second he was in front of her allowed her soft voice to lift up the melody, giving it shape and force. I saw her face wide eyed in awe as she registered the power of the rhythm and harmony they'd created. Obviously, she'd never looked at me like that.

They finished the song and started laughing so intently that to an outsider it would have seemed like they were laughing together.

#

If I'd been confident that I could have beaten Paul in a fight I would have killed him there and then. I closed my eyes and thought of bringing a tomahawk down hard on his head. It was slightly unnerving because my mind wondered, and the tomahawk got stuck in his skull, preventing me from delivering a second blow. I remembered that we have a block splitter in the shed. That wouldn't need a second swing, so I conjured it up instead.

What could go wrong? Did time need both of us to in balance? Would the world start slowing down if the person whose advance balanced my lag was eliminated? I doubted it. Anyway, so what? What has time ever done for me? I couldn't see how losing Paul would make life worse for me.

And I'd still have Susan. Assuming that witnessing me smashing a tomahawk or a block splitter into the top of Paul's head and dragging his body away wasn't a relationship killer. Maybe, I thought, I could do it seeing him out to his car. I was working on the theory that splitting a skull is soundless if the victim is surprised.

I didn't do it. Of course. I couldn't think of an excuse to go to the shed. He was taller than me, so the swing was unfeasible. And anyway, most importantly, he'd be one step ahead. There was no real chance of surprising him.

Just before I opened my eyes, I visualised Susan leaving me for Paul, so that when it happened I wouldn't be shocked, and I’d be less upset.

#

I spent the next week making sure that the house is clean, and all of my things were tidy, in case I had to move out suddenly because Paul wanted to move in to spend more time with Susan.

Occasionally Susan asked me why I was sad. I just talked about being under pressure at work, and she lost interest after a while. She wouldn't understand that I totally accepted the rationality of her trading someone who is always half a beat behind for someone who is half a beat ahead.

#

On the weekend, when Paul came around, I was in the middle of the last set of chores to set the house right. Cleaning the gutters.

He saw me on the roof above the front door and waved cheerfully as he went in. I thought about dropping the leaf litter on his clean, crisp, white linen shirt, but realised that I'd miss him, and wondered if he'd decided to tell Susan he was moving in.

After a while Paul and Susan came out of the back door of house to look at me. The dogs sat neatly and attentively next to Paul on our back deck. I had just finished the south side of the house and was straddling the apex of the roof and bracing myself so I couldn't fall down the slippery tiles.

"Your legs are looking a bit shaky up there mate," said Paul. He was right. Among my many other fears is a fear of heights.

"Go up and give him a hand Paul," said Susan.

On queue, he quickly and adroitly climbed the ladder and stood alongside me.

"What do we do next?" he asked.

I gesture to the north side of the house. "We should go down there and clean the gutters?"

"What are we waiting for then?" said Paul.

I looked down the roof. Its pitch was only as steep as the south side of the house that I'd just negotiated. But the drop from the roof this side of the house was a full two storeys, and my brain just wouldn't let me do it.

"Can I ask one thing first?" I said.

"Yes," said Paul

"Why?"

"What'd you mean why?" said Paul. "Presumably you're up here because the gutters need cleaning. Everyone should be able to do it, but I guess like everything else it's hard for you apparently."

"Not the gutters Paul." I sat on the ridge cap so my legs didn't wobble. "Why do you want Susan? You don't need her," I said. And you know I do, I thought.

"Oh, I don't really care for Susan," he said. "But once I'm with her I think you know what you'll do. You might not admit to yourself that you're committing suicide. But you'll cross a road at the wrong time, or forget to slow for a light that's green and might turn yellow. And then I'll be free of you. I won't be dragged back by your deadweight. I won't be just a little ahead of everything. I'll really be able to fly."

#

Call me stupid, but I'd never looked at the situation through Paul's eyes. He was smart, he'd probably known I balanced him for as long as I'd known he balanced me. I'd thought about what would happen if I killed him, and he'd thought about what would happen if I was dead.

There was one obvious difference though. My tomahawk/block splitter fantasy was about keeping my modest world intact. Paul wanted power. More power. Maybe it wasn't even an accident that we'd met at the football that afternoon. Had he sensed me and hunted me down?

And on that point I realised that I'd misunderstood him. I'd assumed that he'd wanted Susan when he saw her at the football, and was going to take her just because he could. After all, I was used to people taking things from me simply because they could. But as he'd just made clear, he didn't want Susan at all. Her life was just collateral damage in his quest to eliminate me from his world.

You have probably realised by now that I'm not quick to anger on my own behalf. But this casual treatment of Susan's happiness made my blood boil.

#

Paul laughed and took a big confident step off the ridge of the roof.

He looked back at me, maybe to see a final wave of humiliation cross my face before I shuffled off to my future car accident. But his foot slipped on a loose tile, and he started to unbalance.

I don't know why, but instead of crouching and dropping his centre of gravity so a tumble would turn into a harmless slide, he held out a hand and arm for me to help him regain his balance.

For the first time in my life my backwater of time worked in my favour. I reached for his outstretched arm. Too late. Predictably. Perfectly.

After grasping the thin air where my hand should have been, he lost control of his momentum and toppled down the roof and over the edge of the eaves.

I heard a satisfying crack as his head hit the concrete two storeys down. A split skull wasn't soundless after all.

Susan came running from the house. "What just happened?" she yelled.

I held my hands against my chest, trying to sense if anything felt different. "I'm not sure," I said.

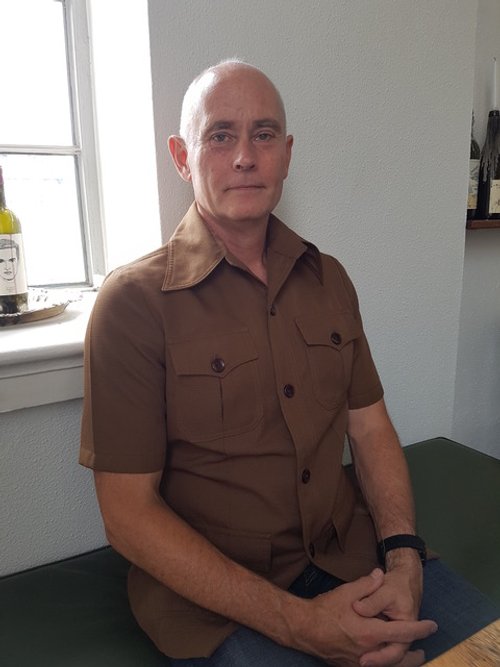

Nick lives and works in Canberra, where he ties to balance his time between the city and the coast. His fiction has been published in Antipodean SF, Cicerone Journal, The Colored Lens, Samjoko Magazine, and The Space Cadet Science Fiction Review.